I.

Tenant lost him job

Him sit down for house

Him dey think of job

Mr. Landord come wake am up

He say, “Mister, pay me your rent!”

— ‘Trouble Sleep Yanga Wake Am’ (1972), Fela and the Africa 70

‘Trouble Sleep Yanga Wake Am’ trickles from the car CD player as we turn onto Bourdillon Road from the Lekki Ikoyi bridge. It is 7:30 am, and as every single morning of the school term, we’ve extricated ourselves from bottleneck traffic, only to get to school minutes late.

We are perpetual latecomers, my children and I. Early morning heat and humidity attack the car windows, until we are ensconced in a bubble of dribbling windscreen and frigid air from the AC. I am telling my children that they must listen to Fela Anikulapo Kuti to enter that experiential knowing, fundamental to being or becoming Nigerian.

I realise I am confusing them. Learning has already begun in the car. I console myself as we silently drink the notes. Everyone is tired. I’m at the steering wheel. Children in the back. Always tired, every single morning. But we are conscientious in how we navigate the privilege of cruising in a beautiful, air-conditioned car to school in Lagos, Nigeria. I am lecturing them, because the country that we lived in for the formative years of my children’s lives often manifested (and still manifests) as a chronic condition that one has to make a strong effort to disambiguate for children as early as possible. As a matter of urgency. Daily.

My children query me on what these words mean. What was the point of the sorrowful humming? Preface to the melody dragging its feet like a dirge…brooding, steaming satire, a seam ripper ponderously taking wonky stitches out of one’s reasoning. The unrelentingly bleak, throaty mourning of Nigeria’s heartbreaking living conditions. ‘Trouble Sleep Yanga Wake Am’ is a slow microscopic passing over of the fragments of ordinary Nigerians daily lives, expanding, dissecting. A 1972 song so prescient, it could have been written this morning in 2025. It was almost assuredly above my children’s pay grade.

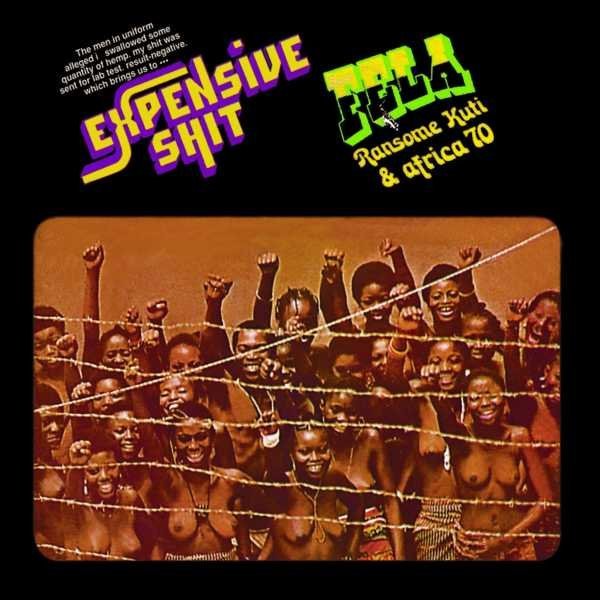

When I was around my children’s ages in the 1970s, my father owned an eclectic vinyl collection: Rice And Beans Orchestra’s Music in the Air; Donna Summer’s Once Upon a Time; Fela Kuti and Afrika ’70’s Expensive Shit; Rose Royce’s In Full Bloom; Millie Jackson’s Feelin’ Bitchy, etc.

My mother warned me sternly against listening to Fela Kuti’s music. She zeroed in on him in a collection that offered a full rack of adult, and often inappropriate, earwigs. He was taboo with a special diplomatic pass for my parents. Since we all lived in the same house and were usually around when my father played his music, the warning translated into a confusing content warning, that only made my ears perk up more earnestly when Fela’s music came on. My mother said unequivocally that Fela had a hypnotic, exploitative power over young women, and his music made innocent girls fall into his bed first, before ending up as one more athletic, gyrating female form in his band, intellectual identity tragically nullified. Did I want to end up a backup dancer? Was that to be the point of my existence?

My mother and I are eternally at philosophical odds. If we used makeshift terms, she would be the cynical feminist relapsing into cultural language when it suits her, and I would be the obdurate culture defector. Yet I agree with most of her feminist-leaning critique of Fela. It did not stop me from visiting the shrine as an adult, where I confirmed her concerns on Fela’s drug use and the morphing of what was supposedly home-and-heath, into a precarious ‘shrine’ arena, swarming with inebriated men and women (and minors). Fela’s home(s) were documented enough times in newspapers, turning into horrifying crime scenes where violence or even death occurred. It was not an exaggeration to say it was a hazardous place to hang out.

II.

Cameroonian journalist Ntone Edjabe says that Fela Anikulapo Kuti needs a whole study curriculum. I agree, but the corollary is that we must be honest about who we are studying. The crux of my mother’s speech was Fela’s treatment of women. And this subheading in the Fela curriculum isn’t one that Nigerians particularly like to contemplate. Ntone Edjabe claimed in an interview in August 2020, there were, “…at the last count …nine books on Fela written by Nigerians and others who lived in Nigeria. This is not the usual musicology stuff. This is people feeling that the story is relevant to them and the last thing they read…they did not find themselves in the last thing they read.”

As Nigerians, we generally prefer to approach Fela as a cultural monument that we delicately, indulgently analyse at best. We laugh when we say his lyrics are marijuana-fueled. We often circle Fela around with disingenuous cultural parameters. We rarely ever discuss his significance to discourse on Nigerian women, especially in the capacities he most revelled in: as a freedom fighter and activist. We acknowledge his brilliance and indispensability, his unparalleled ability to organise and articulate our national pain and dysfunction in penetrating, prescient song and rhythm. We applaud his ability to create musical vocabulary that crosses all the economic and educational gradings of our society.

Fela sang what we didn’t dare to say.

Osenu senu (bonbo)

Osenu senu (bonbo)

Obasanjo senu (bonbo)

Bonborobo (bonbo)

Na benbe na u you go talk oh

Osedi sedi (benbe)

Osedi sedi (benbe)

Abiola sedi (benbe)

Benberebe (benbe)

Benberebe (benbe)

— ‘Underground System’ (1992), Fela Anikulapo-Kuti and Egypt 80 Band

Fela leveled the perspective as all competent prophets do, so that the man on the street, and the billionaire in his Ikoyi penthouse, sang one tune without diffidence or arrogance. He was Peter Fluck’s Spitting Image or Matt Stone and Trey Parker parodying Donald Trump in South Park. His lyrical civil disobedience was meritorious. His voice will probably never be successfully emulated, not even by his less prodigious progenies. But his treatment of women was appalling. We need to admit it into the curriculum. Particularly, distressingly appalling.

On my first sighting of Remilekun Anikulapo-Kuti’s 2024 memoir, succinctly titled Mrs Kuti, published by the Cognix imprint of Ouida books, I was intrigued that we had one more book supporting the Fela curriculum, and this one from an insider who knew him in both private and professional capacities.

Fela was surrounded constantly by women, both at home and at work. And Remi Kuti was the first of 28 wives in a mind-boggling melange that included indeterminate relationships with more women who were not his wives. Who entered and exited his life without restraint or protocol. In explaining and perhaps tidying up this unusual state of home affairs, Fela, in his lifetime, branded himself a practitioner of polygamy, and often orated on the brand by including cultural variables on being authentically African, or pan-African, or eschewing colonial ideas of marriage, and power balance in relationships between men and women. His philosophy was that ‘African’ men could marry as many women as they wished, and women’s opinions were broadly irrelevant. Women could never be equal to men. It is important to say here that the women who had relationships with Fela mostly did so of their own volition.

In Carlos Moore’s Fela: This Bitch of a Life, one of Fela’s wives speaks:

‘Carlos Moore: When did you first meet Fela?

Ihase (Fela’s wife): The first time was when he came to Benin to play, 1973…I learnt that girls stayed in Fela’s house, that he kept girls in his house…Right straight from the stadium I wanted to go with him to Lagos…my brothers wouldn’t allow me to go that night. I was still in school then, ’73, ’74, ’75, Class Three then…So I took 28 naira from my father’s pocket and ran to Lagos.’

— Carlos Moore, Fela: This Bitch of a Life, Page 231

‘The Queens’ first objective is to keep their husband satisfied. Failure to do so may mean their being refused the sharing of his bed when their turn comes up’

—Carlos Moore, Fela: This Bitch of a Life, Page 177

Significantly, Moore noted that many of Fela’s ‘Queens’ were young girls who left home and went to Fela because they believed he was the opportunity and location for the exploration of their adolescent dreams. I must underline here the word ‘adolescent’.

In Nigeria, we often claim that polygamy is, in fact, our true culture. We haven’t yet committed to a thorough academic investigation of the fallouts of the spousal arrangement. Or the effects of inserting adolescents into polygamous institutions. Many of the old-world societal rationales for polygamy, such as large farms needing plenty of familial labourers or the consolidation of peace between territories by marriage, have disappeared a long time ago.

Polygamy is very much a manly romantic ideal that we hit into place by using the legitimacy of traditional customs. Part of recent trends of re-exploring and returning to what we claim are our preferred traditional beliefs and religions, to Africanism, and the way our fathers conducted business, as a way of righting the long-standing ailments of colonialism and our identity crisis, includes the dusting off of artefacts of polygamy and giving them the intellectual gloss that they have long deserved. But polygamy is universal in Nigeria, and post-colonial cultural beliefs and common law provisions on marriage have never contradicted this fact.

In the beautifully arranged anthem ‘Lady,’ one of two tracks on Fela’s 1972 album titled Shakara, (‘Lady’ was re-arranged and recorded to acclaim by South African Jazz musician, Hugh Masekela), Fela offers an unambiguous memo on his views on women.

“ If we call a woman African woman no go ‘gree o

she go say, she go say I be lady o’

She go want take cigar before anybody

She go want make you open door for am

She go want make man wash plate for am for kitchen…”

—‘Lady’ (1973), Fela Ransome-Kuti And The Africa ’70

He also famously sang on “Mattress” that “…the woman’s function in life is to serve as a mattress for man who lies on top…for rest.”

Remi Kuti, in her memoir, wrote extensively, imperfectly, on why she married Fela. She was assigned two chapters in Carlos Moore’s seminal biography on Fela. In Moore’s biography, her first chapter is positioned like a worthy honorarium many chapters ahead of the other wives, whose joint section is introduced by chapter 20 titled ‘My Queens’. Yet the title of the first chapter is ‘Remi, The One with the Beautiful Face’ and the reader wonders whether the homage is trustworthy, especially if one wanted to be contentious and bring in Sandra Izsadore, who was usually described as an intellectual, mentoring female in Fela’s life, i.e. Sandra, who gifted Fela his politics, etc.

Remi Kuti married Fela at age 19. She is the only woman out of his collection who married him as an equal. This statement may be argumentative, but what Remi Kuti’s book presents is a cerebral assessment of her spouse that stands in contrast to the adolescent refugees discarding common sense and education to follow a significantly older popstar. Hers is a unique thesis on being married to the Nigerian national treasure, who is, in turn, infamous for being married.

In the book she describes his youthful eccentricities—his clothes (we are used to seeing Fela in briefs), his wooing, his French-kissing, his broken shoes, his charm—salient details, because she is presenting us a romantic figure that any woman could/would fall in love with, an idealistic rendering that has nothing to do with power or positioning of a man, but his intrinsic feet-on-the-ground appeal. Even reiterated sexual appeal. She tells us he is stupid with women, and we believe her because most followers of Fela’s life know many of the facts surrounding that assertion. But the brilliance of her rendering is that we are carried along.

We know this is a love story that crashes and burns, and we are psychologically prepared for that. She paints a picture of what a Nigerian woman’s sexual desire for a man looks like: For goodness’ sake, a topic that I have probably never read in Nigerian nonfiction without unnecessary self-congratulatory frills, muzzles or stupid titillation. Just matter of fact.

She spars with Fela, dances with him, argues with him, expresses anger, and shows a natural presumed power balance between man and woman, husband and wife. She takes us on a journey that ends at the crucial point of separation. She leaves him, and this point of leaving isn’t only personal, it is political, instructional and an act of public dissent. It is both an expression of strength and an autonomous termination of suffering. Whether she admits in the book or beats about the bush in trying to convince us she is culturally correct and therefore won’t divorce Fela, the act of leaving is counter-cultural.

We know Fela’s mother from history as an educator, a women’s rights activist and a social reformer. She founded the Nigerian Women’s Union in the 1940s, and Fela used to attend meetings with her as a child. We can propose that all Fela’s wives were equal and she was many steps above them. This fits in with time-honoured traditional settings where the mother organises the wives, and all the wives underneath the mother are treated the same (The first wife does have certain pre-eminent rights in polygamy.)

Women presumably treat women better than men do, and understand their own needs better, and often this is the rationale for having a matriarchal figure present (ceremonially or supervisory) in a polygamous household, well, until the first wife ascends to that esteemed role, perhaps when the husband’s mother has died. Fela’s mother was a great ruse for women’s rights in Fela’s life. When she died, one woman did not ascend to replace her, 28 did.

If you thought about it at any depth at all, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti’s son must truly be for suffragists, and there was surely some kind of brilliant, decolonised version of feminism encapsulated in the polygamy practised in Fela’s home. Tradition was masked as progressive Nigerian culture in an extremely retrogressive and damaging cultural arrangement, just as our fathers did it. We move Funmilayo Ransome Kuti respectfully out of the way because she has had her say, and we have a passable understanding of the breadth of her politics on her doting son. On page 204, Remi Kuti makes a pregnant but diplomatic statement about Fela’s childhood:

‘I think Fela had a fear of women dominating him, which stemmed from his childhood.’

—Remi Kuti: Mrs Kuti(Cognix, 2025) Page 204

Remi Kuti is the Mrs Kuti that counts because she is, in fact, the woman who speaks out of turn, as all good women do. She highlights Fela’s mother’s controversial predominance and the performative nature of the Queens. In almost one hundred pages of Carlos Moore’s authorised biography, Fela’s wives speak in their own compelling words, but there is so much missing there. I bring back the idea of Remi Kuti speaking imperfectly in the memoir because the tone of the book is glaringly discordant. One half of the book is spent relating indisputable facts about Fela’s life, some novel, most pedestrian (we know as a nation many of the harrowing details). And the other half, she squanders in trying to convince the reader that the facts bend away from the truth. This insistence on moralising and preaching, especially long paragraphs about the distinctions between ‘Africans’ and ‘others’ to justify her unfortunate decision to marry Fela in the first place, undermines the book and its pace.

“I never understood the women who grew up in Africa where polygamy was not unusual. Some even came from polygamous homes. I was brought up in a society where monogamy was the accepted thing, yet I accepted girlfriends and other wives better than they did (I am not saying I liked him having lovers- I did not!) I also discovered that those girls who demanded Fela should be faithful to them only were the worst offenders for cheating on a man. They all had many other men.”

– Remi Kuti: Mrs Kuti(Cognix, 2025) Page 191

The first forty pages are my favourite because Fela is primarily out of sight and we have an engrossing introspection into Remi Kuti’s childhood and her unhappy time in a children’s home in Sutton Coldfield, a small town near Birmingham, United Kingdom. Her relationships with the sisters who ran the home say much about her intelligence and resilience.

The memoir confirms details about Fela Anikulapo Kuti that we redact as a nation in favour of celebrating his giftedness. I acknowledge that if we didn’t redact them, we might be somewhat hindered in enjoying his gift. We had to excuse Fela’s drug use, his HIV/AIDS denialism, and abuse of women. We mitigated the off-putting, unsightly, public image of an emaciated, unstable man in the uniform of white sagging underwear with lesions from long-advanced disease.

We decided that the women who were his wives and girlfriends were no longer in protective custody of society, having chosen and entrusted themselves to him. Their rights and development were a non-issue and could not be used as a way of determining the effect of Fela’s music and politics on a listening, impressive audience (actively involved in creating contemporary culture) or used to check the temperature of our cultural beliefs where Nigerian women and traditional/modern autonomy were concerned. Mrs Kuti might have been hesitant to admit many things, and the push and pull is visible in the weft and warp of the cloth. One minute she is declaring love for Fela, a kind of maternal cover-all-wrongs kind of love, unsuitable to a spousal relationship, and trying to redeem his politics and behaviour; the next she is showcasing the indefensible, and then attempting to construct a moral compass out of the shreds of her survival, which we can see through all too clearly. It almost, just almost, rubbishes her work, and the editors of the book could have balanced the unsteady emotional feel. Many of the comparisons she was allowed to articulate, made between herself and her neighbours in Fela’s home, or between her children and other people’s children in times of emotional vulnerability, or passages like her riff on Tony Allen, could have been tidied away to give a stronger narrative. Mrs Kuti’s memoir was strongest when she was just telling us her story, minus the sentimental asides and the unbelievable equations like 1 divided by 28 equals satisfied, happy, ‘sexually fulfilled’ and safe.

III.

“If Fela were in Europe, he would be called a male chauvinist’ Mrs. Kuti writes ‘Most African males have inherited the tradition that the men folk give orders and the women obey…My opinion of women differs from Fela’s. Every woman is different, so women can’t be lumped together. Women are not machines from some assembly line. Our ancestors’ approach to women and marriage was not ideal, mostly the women weren’t happy. They were downtrodden, second-class beings.”

—Remi Kuti: Mrs Kuti(Cognix, 2025) Page 253

“Contrary to what many people believe, Fela was a good and caring father. He taught our children so much that will benefit them as adults. So many stars of music and screen all over the world are maladjusted and disillusioned and their kids end up the same. They get into all kinds of trouble, and many end up committing suicide.”

—Remi Kuti: Mrs Kuti(Cognix, 2025) Page 181

Our cultural handling of Fela as Nigerians is problematic. Culture is meant to evolve and not be a stagnant pool yet questioning cultural beliefs can be like wearing a target on one’s back. The answers to the questions are usually accusations of owning a colonial mindset. What do our cultural narratives conclude about men in public spheres, behaving in questionable ways towards women? Should one bother to listen to (pay for) music fashioned by men who offer no substantial advantages to women, no elevation, or even reduce and derogate women in their lyrics and lifestyle?

I am also talking about misogynistic rap music and many notable contemporary musicians in Nigeria. Men in power mishandling young women is an au courant theme. We take it for granted in Nigeria that money and professional success permit men to misbehave sexually and criminally, especially where it concerns young, underage girls. Did Fela have a responsibility outside the limelight to communal ideals outside his social activism or do we judge artists by their work and leave it there? Leave their family dynamics alone? Their flaws, which famous people used to be allowed before social media put everyone’s lives under scrutiny. …Understanding that famous people are inequitably exposed? Why does the pointing out of the grotesqueness of one man divided 28 ways, accessible by rota, cause such cultural pushback? Is a woman who argues with polygamy trapped in a foreign mindset? Do proceeds of activism for economic empowerment, freedom to determine boundaries in relationships, ‘black power’ not accrue to Nigerian women?

The most difficult parts of Mrs Kuti’s memoir have to do with disproportionate statements like ‘Our ancestors lived in communes and Europeans now accept this way of life.’ (and there are inordinate amounts of them in many chapters). Neither grounded by a real location called Europe nor distinguishable people called ‘our ancestors’. These kinds of statements necessitate references to other writings on Fela and erode the broader biographical possibilities of the memoir. We say no one forced the women in Fela’s life to accept the terms he offered them. Nor forced them to remain with him without confirming the state of his health, and these are all the cultural documentation and parameters we need. We even say that many of the things we are venturing into by looking closely at Fela are personal matters. Family matters should be morally out of bounds. When Mrs Kuti says in reference to Fela’s lifestyle that ‘one man’s meat is another man’s poison’, she trivialises her rationale for being with him, or even for ever writing a memoir that places him at the centre. What exactly does that statement mean in any case?

The reason why we are reading the book is exactly because platitudes are useless and we want concrete truths. We want to know what the experiences of the women around Fela were. What was going on in their minds? How did they negotiate the beatings, rape and imprisonment that came with defying the Nigerian army alongside Fela? How did a woman whose formative years were spent in a society that holds monogamy as the highest ideal for married couples end up the mother-wife of a polygamous man with 27 other queens? A crucial part of humanising the artist involves talking about and thinking about their lives and legacy, whether parts of the legacy make us uncomfortable or not. How on earth did the makeshift polygamy work? People want to know what the significance of an artist we call a genius in Nigeria is. How he is still influencing culture, at the risk of being repetitive, especially where it concerns women who he was surrounded by and was carried along by his mother to campaign for.

We say that many of the predictions Fela made in song are with us, so why should his benefactions on women be exempt? The most chaotic and traumatising parts of the book are the pages dedicated to a phantom that entered the narrative and family home by standing half-hidden in the corner of the compound of Fela’s house. She materialised into a violent stalking love interest who was pregnant with Fela’s child. A woman who came and went as she liked and attacked family members. The chapter titled ‘Coping with Girlfriends’ expanded into a sobering reveal of Fela’s impotent cowering to certain women in the system that he created and lauded as progressive, new-African and supremely desirable. In essence, the memoir’s most important achievement should not have been incidental to the purpose of the book because of the yay/nay of the writer. Mrs Kuti lost her balance when she tried to be both victim and cultural police at the same time. Stand for a system whose manifesto has not been codified properly, but also by rights, stand for her sanity, safety and individual ideals. By the time we reach the chapter titled ‘On the place of women in Africa’, the narrative has pretty much lost its integrity in the tug of war, and we continue to read out of good manners, despondent at the lost potential…trodding to the end so we can go away from the text.

My mother wasn’t afraid to bell the unpopular cat in her warning on Fela, that women who chose him seemed to have lost their agency via potent mix of jazz, American blues, highlife, Yoruba cadence and chants called afrobeat plus something else we couldn’t identify. Juju braised in music. Fela did not hide his exploration of the occult, and Carlos Moore did not circumvent the subject. A memoir’s writer in the end decides the height of the ceiling and depth of the basement, but the omission of this major part of Fela’s life and the way his religion informed so much of his music and home and even costume – casts more than subtle suspicion on Mrs Kuti’s memoir and the book’s willingness to really articulate and agree to basic standpoints without shuffling her feet. The intellectual component of this book was crucial but tragically lopsided. Even admittedly so in the words of the memoirist herself:

‘I have tried to write some of the story of my life with a man who was sometimes annoying, sometimes very lovable, and sometimes happy, sad, or angry…I have tried to be impartial and found it quite difficult.

—Remi Kuti: Mrs Kuti(Cognix, 2025) Page 262

The 1975 album cover of Expensive Shit with a photo of Fela and wives, bare breasts absolutely, unavoidably everywhere in view, (designed by Remi Olowookere) was a life-changing encounter for me as a child. I could not settle comfortably on the sofa in my parents’ sitting room, with the album in hand, questioning why on earth women agreed to present themselves in this way. I dared not. …They looked happy…exhilarated. What did the raised fists mean? Why were they standing behind barbed wires? How could shit ever be expensive? (Shit in uninitiated layman’s terms that is). The long interrogation of the matter was something that I carried with enthusiasm into Mrs Kuti’s memoir. There was no way that I could have imagined that 265 pages later, I would still be thirsty for answers.

________

Yemisi Aribisala is a Nigerian author, painter and illustrator working from and living in London.