To discuss To Kill a Monkey without addressing its reception would be disingenuous. The release was a cultural event. Adetiba’s extraordinary fanbase has erupted since King of Boys (2018) established her as a Nollywood powerhouse. To Kill a Monkey (TKAM), which premiered on Netflix on July 18, 2025, represents both a triumph of ambition and a cautionary tale about the dangers of excess.

Adetiba’s reputation as a director who fuses operatic grandeur with a distinctly Nigerian sensibility placed an enormous burden on TKAM. The hype itself became a narrative: social media discourses, meme cultures, and critical hot-takes swirled before viewers had properly engaged with the series. The danger of such hype is that it predisposes audiences to receive a body of work, not on its own terms, but on the imagined standard of its creator’s past glories.

To Kill a Monkey invites comparisons to canonical novels exploring moral ambiguity, such as Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958), where protagonists grapple with systemic forces that erode personal integrity. While ambitious in its thematic scope and visual audacity, the series succumbs to narrative bloatedness and thematic timidity. For all its kinetic energy, it prioritises spectacle over substance, leaving its critique of poverty and cybercrime at best performative.

Like Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, Adetiba’s series exists at the intersection of individual tragedy and societal malaise. Unlike those works, TKAM is less interested in peeling away systemic rot; instead, it stages a melodramatic confrontation between morality and corruption. In doing so, it echoes and subverts literary traditions ranging from the tragic arc of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov to the spectacle-driven narratives of contemporary crime dramas.

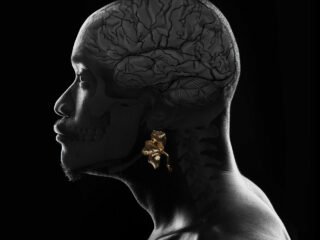

Image credits – Promotional Poster

At its narrative core, To Kill a Monkey dramatises the descent of Efemini “Efe” Edewor (William Benson) from dignified poverty into the corrosive world of AI-powered cybercrime, under the tutelage of the flamboyant Oboz (beautifully portrayed by Bucci Franklin). Efe’s early struggles are painted in broad strokes of deprivation and humiliation. Poverty is not merely material lack; it is existential suffocation. His suffering is visceral and biblical in scope. Its cause is depoliticised, attributed to fate, not the structural bankruptcy of the Nigerian society.

Efe is lured by Oboz’s promise of wealth and dignity, at the cost of his integrity. The monkey mask, that familiar emblem of anonymity in fraud, becomes the symbolic pact, akin to Faust’s blood-signed contract with Mephistopheles. Yet unlike Goethe’s Faust, whose intellectual yearning drives his downfall, Efe’s tragedy emerges from sheer desperation.

Efe’s transformation into a cybercriminal is predictable but elaborately dramatised. The narrative arc echoes Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, where Raskolnikov justifies crime with intellectual rationalisations, only to be crushed by guilt. Efe, however, lacks such interiority. His journey is less psychological exploration, more plot contrivance. TKAM is a missed opportunity to craft a Dostoevskian Nollywood protagonist.

Benson’s portrayal of Efe is constructed as a universal symbol of suffering. His poverty is exaggerated to mythical proportions like a modern-day Job, pelted by misfortunes so relentless. This flattening is problematic. Efe is less of a character and more of a caricature. His underexplored contradictions make his eventual moral compromise less inevitable tragedy than narrative inevitability.

In contrast, Bucci Franklin’s Oboz is a triumph of characterization. He embodies the Sphinxian archetype: charismatic, beguiling and unpredictable. His dialogue, garbed in Benin pidgin, is poetic and improvisational. Oboz reflects the society that rewards cunning over honesty, spectacle over integrity.

Nosa, portrayed with grace by Stella Damasus, embodies the stoic traditional wife whose quiet resentment simmers beneath a facade of endurance. Her evolution from supportive spouse to disillusioned matriarch provides some of the series’ most poignant moments, critiquing the gendered burdens of poverty. Nosa does not emerge unscathed from the trope of the “long-suffering spouse.” She is denied agency; she reacts, rarely ever acting.

Bimbo Akintola’s Inspector Mo could have been the moral compass of the narrative. Instead, she is flattened into a cliché: a widow addled with post-traumatic stress disorder, which hampers the investigative rigour her good cop archetype demands.

Escort turned strategist Sparkles (Sunshine Rosman) and crime overlord Teacher (Chidi Mokeme) are poorly developed characters. Jonathan Haynes noted in his book on Nollywood that there is “only one essential metaphor for talking about plotting: a piece of rope, or it could be string or ribbon, which is “denoue,” unknotted, at the denouement, difficulties unraveled; or the loose ends are tied up, in a pretty bow or a hangman’s noose, an elegant firm containment.” Inspector Mo’s trauma, Ivie’s hatred, and the Teacher’s villainy are hurriedly outlined and abandoned.

Adetiba’s directorial style is maximalist. Each scene is drenched in tension; every camera swoop signals significance. TKAM fears silence more than it fears failure. This results in “cinematic logorrhea,” an excess of style that could exhaust the audience. To be fair, Adetiba’s aesthetic choices are part of a larger Nollywood ethos: to assert the industry’s capacity for spectacle at par with Hollywood and Bollywood. In this sense, maximalism is political, a refusal to be aesthetically modest in an industry often dismissed as amateurish.

Despite its flaws, To Kill a Monkey represents Nollywood’s ongoing negotiation between local storytelling traditions and global streaming expectations. The ambition is commendable; the result is paradoxical: exhilarating yet exhausting, profound in ambition yet timid in execution. It dazzles with spectacle but falters in substance. From a literary perspective, it is a litany of missed opportunities, a Faustian tale that side-steps its most pressing question: Is morality a luxury in a broken society?

_______

Segun Odejimi is a Nigerian storyteller with 15+ years’ experience across journalism, advertising, and marketing – former Chief Editor of TNS, Nollywood podcaster, film awards juror, adman, and Sprinng Fellowship Mentor.